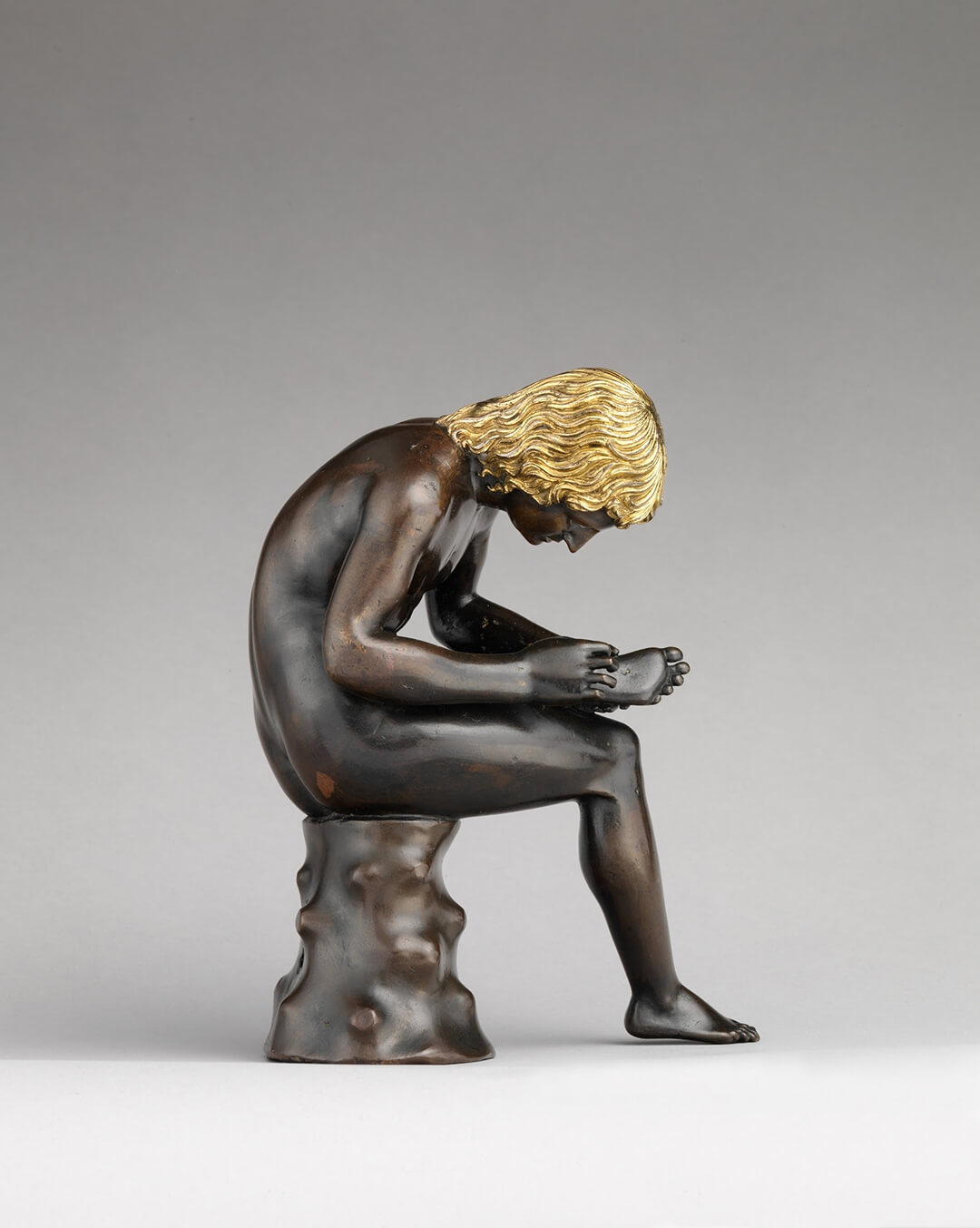

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

By now every new Journal story appears within a tangle of other stories. In fact, recounted from different timelines and geographical locations, these stories didn’t seem to have much in common before. But up close, the tangle of threads seems almost orderly. Just think back to the plaster statue of Athena, in Xu Beihong’s studio a few journal issues ago.

PLASTER COPIES IN CHINA, BRONZE COPIES IN MANTUA

Another story, another artist, and today we’ll meet [drum roll] Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi Gianfrancesco Riccardino (just kidding, those last two names are made up). Better known as: L’Antico (the Ancient). “What’s this, an insult?” No, no. He didn’t simply imitate classical marble statues, plagiarizing in art history’s back room. He kept a workshop in the center of Mantua, during the Renaissance boom. And just a glance at his army of bronze statuettes – sleeping cupids, heroic figurines, deities whose curls swallow up their crowns – is enough to confirm that L’Antico earned his name.

…AND IL MODERNO (THE MODERN)

Every geographical location and every different time period has its own ancient art. Some individuals are so obsessed that they try to recreate it in the laboratory, artfully aging surfaces to give objects the impression of elapsed time. It’s something that has always been done. The Italian Renaissance did it. And people like L’Antico were celebrated. We’ll ponder the reason why another time. For now, we are left with a simpler question: Why was Galeazzo Mondella, L’Antico’s competitor, called Moderno?